- Published Oct 15, 2013 in The Biz

They are the heart and soul of the aural experience integral to every great movie. The fact that you don't notice them proves just how good they really are.

I had a conversation the other day with a young friend of mine, interested in audio, but looking to go into film. He was concerned that there wasn't a career in making movies; that his parents weren't sure he could make a living out of it.

Knowing how genuinely intelligent and motivated he is, I challenged him: "Do you know what goes in to making a movie?" He responded, "Well, I know there's the director, writer, camera guy... To be honest, I'm not sure what else."

In my head, I went through a quick list of roles on a modest shoot, then started diving into post-production. His eyes widened and breath exhaled. Phew! He thought he had to come up with a genius screenplay to get a job in the biz.

Just as with recording music, mic placement is key.

Truth is, I wouldn't recognize a great screenplay if David Seidler handed me The King's Speech in draft form and said, "Hey, can you work this out for me?" But, while I may have had other aspirations years ago, I ended up in audio and it's what I can speak about.

Being involved in production—and post production—helped me list the various options for starting out in sound for film for my young friend, and gave him plenty to arm himself with in his quest to convince his parents he wasn't crazy for wanting to make movies.

Sound on the shoot.

Recordist; Boom Operator

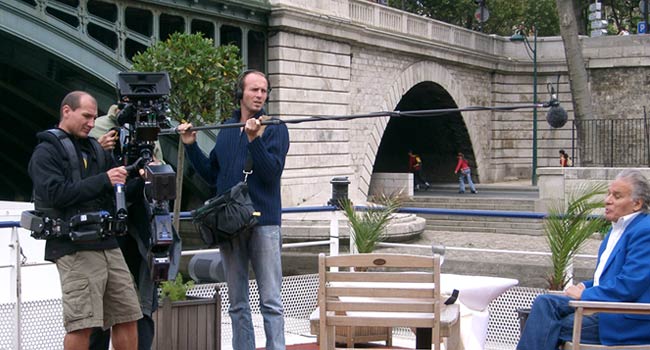

You'll find any number of general production types on a set, from writing to lighting to recording to coffee picking-upping. In audio, these folks are most commonly the recordists and boom operators.

A good recordist is the type of person who knows that having options is crucial in the event you have anything from wind and other environmental issues to an interviewee who can't sit still. Just as with recording music, mic placement is key, though you may not have the time to do it as specifically as you're accustomed to in the studio.

Photo: PRA [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: PRA [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

On small production sets, one person often fills the role of recordist and boom operator.

As a post-production mixer, I have received a lot of badly recorded audio in my day. Yes, sometimes it's the result of extenuating circumstances related to location or weather—particularly when dealing with documentaries where the heat of the moment action can prevent the perfect take.

Other times it's not setting the damn limiter so that it a) isn't hitting the incoming audio's threshold so low, or ratio so hard, that everything distorts; or b) isn't hitting it at all so that the loud stuff always distorts, but the soft stuff is so low it's laden with noisy ambience. An understanding of the basics of compression can easily fix this problem.

What makes you a pro is knowing the equipment and the necessity to run as many tests as possible—either in a rough take on location, or somewhere in the general vicinity where you can get a sense of how the environment is affecting things. I've probably said it in every article I've written:

Get. Good. Sounds.

This is particularly crucial on a job where you may not have the opportunity to replace sounds in post production with sound design and ADR (automated dialogue replacement). A keen awareness of the audio from your shoot is particularly important in documentary-style filmmaking. Clean audio on any film can make the difference between a mediocre movie and a great movie.

It's not always feasible to keep track of every little detail on a hectic shoot. Though sometimes there will be a person on a shoot or set to handle logging, it is the responsibility of the recordist to know what they have and where they have it. This becomes crucial after the shoot when everyone is going from a production to post-production mindset.

As the shoot recordist it's imperative to have a clean log of what was captured and when. However, unless you're on a very small production team, you may not be responsible for getting the audio digitized and/or transferred for the editor.

The production wrap.

Assistant Editor

If you are this person, God bless you. These folks definitely deserve to be listed among the unsung heroes of filmmaking. These are the people who know more about the footage than anyone in the production process. Logging, transferring, and prepping for the edit can be mundane on the best of days and catastrophic on worst.

Between multiple overnights, crashing hard drives, overtaxed computers, and overdoses on caffeine and pretzels, when all is said and done, they will be responsible for getting hundreds of hours of footage from the haphazard labeling of shoot logs to a paired down, sussed out, orderly edit session for the editor to then take over. Many times the director, editor, and others will be involved in this process, fishing through takes and shots, and compiling the scenes they want available for fine tuning.

Assistant editors are oftentimes so close to the process that they become integral in not only the prep work, but in the edit itself. This awareness and knowledge of the footage is extremely important during the editing process, and can be a real savior in the event no one else has the answer to a shot or sound question in the edit. Coming through with that key piece of information can be quite rewarding, and truly create a scene.

Time for post.

Audio Editor; Sound Designer; Foley Artist; Mixer

Once the edit is done—or you have some incarnation of a film in sight—the audio side of post-production comes into play. In many instances, this is the last major step before the movie is finished.

The foley artist creates sounds heard on screen by recording themselves banging, stomping, running, thumping, pedaling and swinging whatever the scene requires.

On bigger budget movies, more work is done on titling and color correction before it goes to the big screen. For smaller films though, much of this is done by the editor. However you shake it, once you're in post audio, you're in the home stretch.

First, the audio editor gets to the nitty gritty. Cutting dialogue, building environmental sounds and backgrounds, and smoothing out the various ambience in between. The audio editor may also have to add or swap out audio from the shoot, thus they may have access to the digitized footage and logs. The audio editor is often close to the editor and assistant editor as they need to be able to access things efficiently.

The sound designer and foley artist are responsible for fine tuning the sound environment. The foley artist creates sounds heard on screen by recording themselves banging, stomping, running, thumping, pedaling and swinging whatever the scene requires. A hammer thwacking a watermelon could be the sound of a guy throwing a punch, the smack of a metallic aluminum sheet could enhance a thunderclap. Whatever the scene entails, the foley artist must comes up with creative ways of making a sound in a scene work.

The sound designer, on the other hand, compiles the sounds from the foley artists along with importing their own sounds from the sound libraries studios often have in-house. It's their job to piece all of these elements together and create the soundscape of the film. It's a big task: when done well, their work sets the mood and creates believability in worlds realistic or fantastic.

If it's done poorly, though, it can come across as too over-the-top, underwhelming and skimpy, or just plain inaccurate in relation to what's being presented visually. The goal first and foremost: support the visuals.

Re-recording mixers do what their name implies: re-record dialogue in the studio to replace audio recorded on a shoot. As I mentioned before, this is much less common in documentary-style filmmaking, but is very common in major films.

Photo: Victor Grigas [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Victor Grigas [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Audio post production is often the last major step before a movie is finished.

Because of the limitations of shoot recording, sometimes its necessary to get a re-do to really make sure a line comes out cleanly in the mix. The re-recording mixer's job is to record an accurately synced take and mix it into the rest of the dialogue in such a way that it sounds like it was recorded on set. This requires a solid handle on the intention of the ADR and the technology used to process it.

The re-recording and post mixers work together to put the final brushwork on the film. These are often split up into a few sub-roles: dialogue, sound effects, and music mixers. On smaller films, however, these can all be consolidated into a single role. They put the final stamp on the piece, compiling all the elements, using volume, effects, and their well-trained ears to build a beautiful juxtaposition of audio elements.

Off to the show.

Sound for visuals isn't as simple as it seems. In fact, it's generally a lot messier! That said, the process can be incredibly rewarding. So many outstanding movies don't get the attention or recognition they deserve because sound was either ignored or only thought of in passing. The best films are always aided by someone with an ear for great sound.

Working in sound is a great way for people who, like myself, want to make a big impact on a production without necessarily being front and center. In that sense, sound is only a slice of the production pie, as hundreds of people can contribute behind-the-scenes in their own meaningful ways. Whatever your interest is, I hope you learned one thing: when it comes to audio for visuals, there's more than meets the eye.

One last thing.

I left out composition and scoring because I wanted to introduce the capturing and prepping of shoot-related sound. The music in a film plays an equally critical role, and presents another host of options for audio people looking to get involved in motion pictures or television.