- Published Sep 9, 2013 in Music 101

Respected musician and educator, Marc Rossi, looks at the links between Jazz and Classical Indian Music.

Jazz and Indian classical music—two of the great musical idioms of the world—at first would seem to have little in common. Indian music, with roots going back thousands of years, developed in the courts and temples of India, and now is performed in concert halls around the world.

Jazz, with its diverse beginnings in jam sessions, the black church, night clubs, and even brothels, was forged in the cauldron of 20th century segregated America in such places as New Orleans, Kansas City, and New York, and is now heard as well in concert halls around the world.

Yet when one examines them closely, we see just how much these musics have in common as modes of human expression, paths for spiritual advancement, and in the realm of pure music itself. We then can see just how much Indian music has influenced jazz, and will continue to do so on many levels.

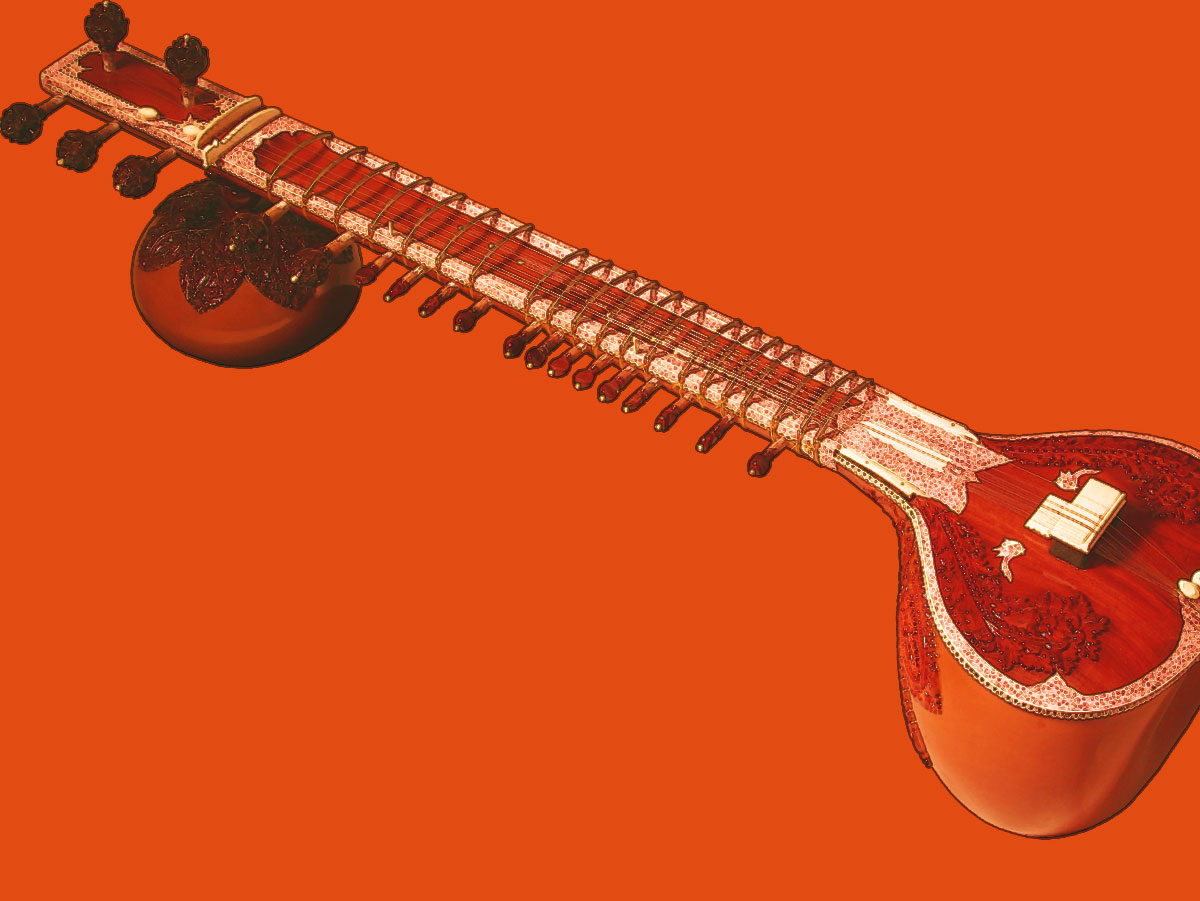

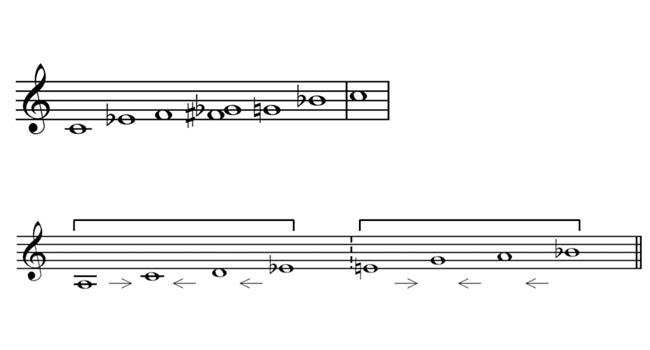

An example of early Indian Bhat music notation.

Indian music's influence on jazz is pervasive and longstanding. Its beauty, grace, and unique melodic phrasing has inspired musicians for decades, and its exciting rhythmic language has given percussionists, instrumentalists, and even vocalists new resources upon which they have drawn. Its philosophical underpinnings have allowed many musicians to deepen the spiritual aspect of their music. For many jazz musicians the influences have been personal, at times abstract; informing their musical choices, but not always in a manner overtly apparent to the listener. For a few however, the influence is so strong, it is immediately apparent at every level of their music.

Types of Indian Classical Music

There are two main types of Indian classical music: Hindustani (North Indian), and Carnatic (South Indian). Hindustani is considered more romantic and expressive in nature, and Carnatic is more like classical or baroque. Both systems use ragas (melodies based on scales) and talas (rhythmic cycles), but in different ways. Both systems allow for extended improvisations and dazzling displays of melodic and rhythmic virtuosity. The beginning listener might find them somewhat similar since both systems have a drone accompaniment (like some early Western music), but after a while, one can easily tell the difference.

Hindustani music has always been more popular with the public because of its aesthetic appeal and association with 1960s rock culture.

North Indian music favors simple repeated compositions that serve as vehicles for extended improvisations, while South Indian music is based on a repertoire of extended compositions called Kritis—art songs that are learned note for note. It would be impossible to have a Hindustani performance without improvisation. It is, however, possible to have a Carnatic recital where the songs are performed with little or no improvisation, though more often than not, that is not the case.

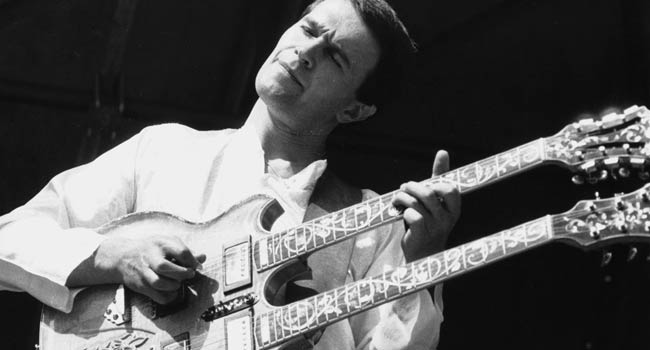

Some well known Hindustani musicians include the famous sitarist Ravi Shankar—a true superstar; the late sarodist Ali Akbar Khan, who founded a school for Indian music in Marin County, California; and tabla player Zakir Hussein, who has played with Indian greats and Western musicians, and can be heard in numerous film soundtracks.

Some well known Carnatic musicians include violinist L. Shankar (no relation to Ravi) who has performed with rock singer Peter Gabriel among others, and his brother L. Subrmaniam, who has performed with many Western classical and jazz musicians, including major symphony orchestras, and jazz pianist Herbie Hancock.

Hindustani music has always been more popular with the public because of its aesthetic appeal and association with 1960s rock culture, and the sheer number of performers who play it. Carnatic music, now growing in popularity, has always had a foothold in academia, because it is highly organized and tends to be taught in a more systematic way.

Indian music in the west.

Indian music (Hindustani) was performed in the United States as early as the 1930s by musicians in the dance troupe of Uday Shankar, older brother of Ravi Shankar. Uday and his troupe were based in Paris, but toured the world. Their performances were usually for a small select audience of cognoscenti.

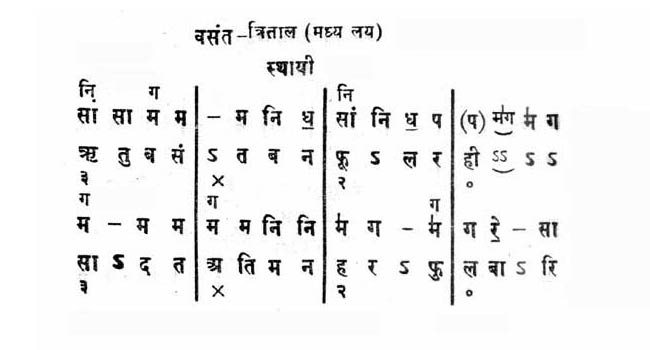

George Harrison, who studied with Ravi Shankar, brought the sound of traditional Indian music to The Beatles and a new era of popular music.

However, sitarist Ravi Shankar is almost single-handedly responsible for popularizing Indian music in the West, in part through his brilliant showmanship and ease performing for Western audiences, and in part because of his association with George Harrison of the Beatles. The Beatles included sitar (and tabla) in some of their songs, most famously the sitar melody in Norwegian Wood, played by Harrison himself, who studied with Shankar in 1966.

By that time Shankar was performing for large audiences in concert halls and at major music festivals, including the famous Monterey (California) pop festival of 1967, and was almost a pop icon himself. The hypnotic buzzing sound of his sitar, rich in overtones, was a natural acoustic ally of the electric guitar sounds of that era.

The highly expressive melodies and extended improvisations played by Shankar and his longtime tabla player Alla Rakha were a good fit with the extended jams of rock groups such as Cream, (who cite Indian music as a direct influence), Jimi Hendrix, The Grateful Dead, The Jefferson Airplane, The Doors, and others. Think of the lyrics to Eric Burdon's song Down in Monterey,

...the Grateful Dead, blew everybody's mind. Oh, Ravi Shankar's music made me cry.

Ravi Shankar was a household name to '60s music lovers, and to many, synonymous with Indian music.

This presented something new and exciting for Western popular music audiences, and for serious musicians—a gold mine of new language and beauty. It also reflected the openness of that era, where people were seeking new experiences and expanded consciousness.

Needless to say, drugs and psychedelia played a part in this openness and in looking beyond the ordinary, but only in a superficial manner. This was a purely Western phenomenon of the times, a unique product of rock culture because, in reality, Indian music and drugs are polar opposites. However, Indian music has much in common with yoga and meditation, which also were becoming popular in the West during that era, as ways of expanding one's consciousness.

From the jazz perspective it's important to note that the extended modal improvisations of Miles Davis on his famous "Kind of Blue" recording of 1959, as well as those of saxophonist John Coltrane, composer George Russell, and others, opened up new territory in jazz. These musicians were getting away from the standard jazz repertoire of Tin Pan Alley songs, and exploring playing on the scales themselves via extended improvisations, much the way Indian musicians do.

Miles Davis in session with John Coltrane, Canonball Adderley and Bill Evans embraced modal improvisation popular in Indian music.

This requires great skill, and is far more than just jamming. These modal jazz explorations began in the 1950s and continued to develop in the '60s, overlapping perfectly with Ravi Shankar and the progressive rock groups. Groups like the Doors cited that Miles Davis was one of their influences. The famous organ and guitar solos on the album-length version of Light My Fire are based on the Dorian mode, and have much in common with Miles Davis' So What, also based on the Dorian mode.

This mode is also very common in Indian music, both North and South. In North Indian it is the scale of rag kafi, a very popular Hindustani rag, and in South Indian, the scale of raga karaharpriya. This process shows how much common ground Indian music, jazz, and even rock can share, starting with the most basic elements.

Influence on Jazz musicians.

In my opinion, among major jazz artists most directly influenced by Indian music, the two best known are saxophonist John Coltrane, and guitarist John McLaughlin. Two different generations—Coltrane the grand master steeped in be-bop and traditional jazz, eventually defining the avant-garde and transcending the idiom itself. McLaughlin, a jazz innovator who embraced electricity and Rock, and spearheaded what became known as the Jazz-Fusion movement. Both are consummate virtuosos hugely influenced by Indian music, and both opened the door for others to follow.

Coltrane was influenced mainly by Hindustani music—he befriended Ravi Shankar, and even named his own son Ravi. Coltrane's famous quartet with pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones—one of the most influential jazz groups of all time—explored the extended modal improvisations and time frame found in Shankar's music.

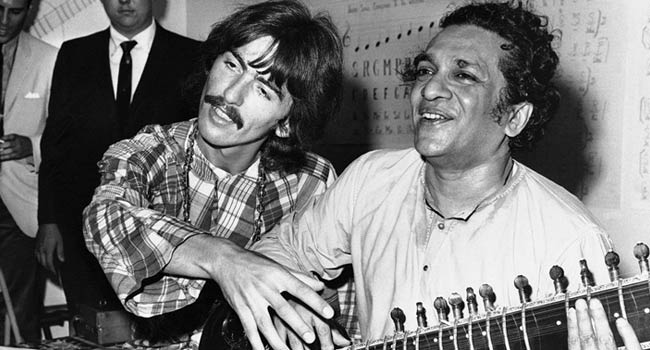

John McLaughlin, credited with spearheading the Jazz Fusion movement was hugely influenced by Carnatic Indian playing and composition.

McLaughlin's influence has been mainly Carnatic, as is evidenced by his groundbreaking electric group The Mahavishnu Orchestra, and his later acoustic group, Shakti. This group included Carnatic violinist L. Shankar, tabla player Zakir Hussain, mridangam player R. Raghavan, and ghatam player T. H. "Vikku" Vinayakram. Though Shakti also had Hindustani elements due to the presence of Zakir Hussein, the great sarodist Ali Akbar Khan expressed his view to me in 1975, that "McLaughlin's style is more South Indian." (Ali Akbar Khan was considering performing with him at that time.)

Indian music and spirituality.

It is important to note that many jazz musicians' interest in Indian music was intrinsically connected to their interest in yoga and Indian spirituality. Coltrane and McLaughlin, as well as bassist/composer Charles Mingus, flutist Paul Horn, and quite a few others, are not exception. Coltrane was interested in many eastern religions, and his second wife Alice, a jazz pianist, became a senior disciple of Indian guru Swami Satchitananda.

As jazz reached back to African music, it also discovered Indian music and philosophy.

McLaughlin was a disciple of Bengali guru Sri Chinmoy and wore a picture of him on his shirt as he performed during the Mahavishnu period. Mingus wanted to be cremated, and even had his ashes spread over the Ganges river—something often done by devout Hindus. Paul Horn recorded solo flute inside the Taj Mahal in India, and was one of the first teachers of Transcendental Meditation (TM) in the US. (In 2009 he performed in Radio City Music Hall, alongside Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, to raise money for the David Lynch Foundation, which teaches the TM technique to at-risk children.)

As part the social transformation happening in America during the 1960s and 70s, jazz also began searching more deeply for it's own roots beyond the dominant Euro-American influences, and that created an interest in African music and culture, and world music in general. As jazz reached back to African music, it also discovered Indian music and philosophy. These non-Western assimilations ran concurrently, and continue to this day.

There are today a growing number of musicians for whom Indian music is a part of their musical lexicon—not something exotic, but an ongoing stream from which they continuously draw. As Transcendental Meditation founder, the late Maharishi Mahesh Yogi said, "It's not about East or West. Take the best of the East and the best of the West." Personally, as a practitioner of TM myself, I love this philosophy, and try to follow it.

Elements in common.

Melody, rhythm, and harmony.

Both Indian music and jazz have melodies based on modes, (scales or ragas), pulse-oriented rhythms, (played by drums) and improvisation, all of which have been developed to a very high level. A serious listener can be transported to great heights by such artists as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, L. Subramaniam, and Pakistani Qwwali singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, whose legendary voice can be heard on the soundtracks to Dead Man Walking and Natural Born Killers. The same can occur with jazz, when performed by artists like John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Keith Jarrett, or John McLaughlin, to name just a few.

As Indian music found its way into popular Western culture, artists like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan could be heard on the soundtrack to movies like Natural Born Killers.

In addition to melody, both Indian music and jazz employ harmony and tonal color. Indian music maintains a more static harmony—the color of the raga against the drone, with nuanced melodic phrases that bring out these colors. Jazz also is rich in harmony and color, but as in most Western music it is based on progressional harmony—a sequence of chords—which often change key, or tonic. The jazz soloist must relate melodically to this flow of color, much the way an Indian artist does when playing what's called a ragamala, literally 'garland of ragas,' that is, several ragas in sequence.

In fact, for Indian listeners, jazz is often compared to a ragamala, with some pieces going through many changes, and some only a few. The difference is that in Indian music, even in a ragmala, the drone remains the same, whereas in Western music, the "drone" itself, or key center, usually changes.

Modes, scales and ragas.

Regarding the use of Indian modes, jazz historian Lewis Porter in his book John Coltrane: His Life and Music, quotes Coltrane as saying:

I like Ravi Shankar very much. When I hear his music, I want to copy it, not note for note of course, but in his spirit. What brings me closer to Ravi is the modal aspect of his art. Currently, at this particular phase I find myself in, I seem to be going through a modal phase...There's a lot of modal music that is played everyday throughout the world. It's particularly evident in Africa, but if you look at Spain or Scotland, India or China, you'll discover this again in each case.... It's this universal aspect of music that interests me and attracts me; that's what I'm aiming for.1

Porter goes on to say,

"It wasn't only the sound of world music that attracted him; Coltrane was interested in all kinds of religion, and in all kinds of mysticism. He knew that in some folk cultures music was held to have mystical powers, and he hope to get in touch with some of those capacities."2

Western classical music had ceased using a variety of modes during the common practice period, and used mostly the major and minor scales from which melodies, harmonies, and form were derived. But modes were re-introduced to the West by 20th century Western classical composers such as Claude Debussy, Bela Bartók, and Igor Stravinsky. Jazz, being a 20th century music, adapted many of these modes, including the blues scale—a six-note scale entirely unique to African-American music.

Photo: Hyacinth

Photo: Hyacinth

The blues scale as minor pentatonic plus flat-5th followed by a blues scale as used in jazz, divided into two identical tetrachords.

As jazz developed, it was natural for musicians to explore the rich array of scales in the Indian raga system and bring them into the jazz fold. In addition, the use of expressive melodic pitch bends and embellishments as found in Indian music has influenced jazz-fusion and rock, to a great extent.

Both guitarist McLaughlin and synthesist Jan Hammer, a fellow founding Mahavishnu Orchestra member, cite South Indian veena master Balachader as a major influence. (Veena is a South Indian plucked strung instrument.) You can hear this in the nuanced pitch bends of their individual playing, and in their famous guitar-synth trade-offs, exchanging blazing lines at ridiculous tempos. Along with McLaughlin, Hammer was a pioneer in this type of playing, and dramatically increased the expressive potential of the keyboard player, something very close to my heart.

The drone.

The sheer hypnotic sonority of the drone, played by the tanpura, has also been a strong influence. Music journalist Ashley Kahn in his book A Love Supreme; The Story of John Coltrane's Signature Album, quotes Coltrane as saying to Dutch reporter in 1961:

I've been listening more and more to Indian music—I've been trying their methods in some of the things we're doing. I wanted the band to have a drone [sound, so] we used two basses.3

Like languages, both jazz and Indian music have grammar, syntax, and vocabulary, and despite their differences, share many sonic elements in the context of human musical expression.

Composition and form.

As noted earlier, North Indian music is comprised of compositions that are often simple repeated phrases based on formulas that serve as vehicles for improvisation. Jazz also employs similar short compositions, usually a melody with chord changes that also serve as vehicles for improvisation. South Indian music uses extended compositions (Kritis) that are a main part of the repertoire, and jazz also has a similar repertoire of extended compositions that are played verbatim. This alone reveals a tremendous amount of common ground and conceptual unity between Indian music and jazz.

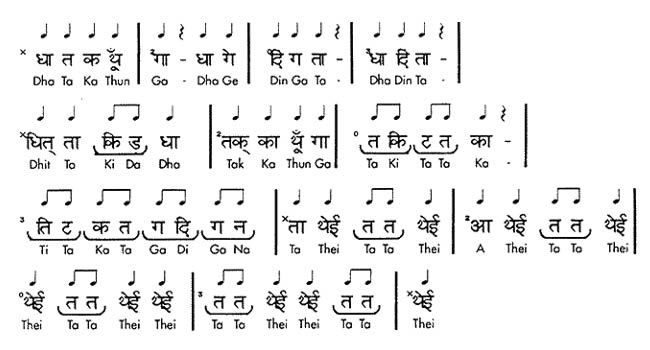

Traditional tabla rhythms, made famous in Western music by tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussein.

But no matter how much the composed repertoire may be performed, improvisation is an intrinsic part of both genres. This is evidenced in North Indian music in both the alap (opening free-time section without drums,) and bandish (composition section with drums), and in South Indian music by the alapana (S. Indian name for alap) and the kalpana-swaram (note improvisation) and nirnival (improvisation on the lyric) sections.

In Jazz, improvisation is always expected. Both genres are very much in-the-moment art forms requiring spontaneous music making, and both require years of serious discipline and study before one can play them well.

Rhythm and time.

Another important way that Indian music has influenced jazz is in the use of complex and odd metered rhythms. The tala systems—both Hindustani and Carnatic—are rich in their variety of rhythms, and their almost endless capacity for permutation and development. Until the 20th century, most Western classical music was in 4/4 time (like Hindustani teental or Carnatic adi talam) or 3/4 time (similar to Hindustani dadra or Carnatic rupaka talam.)

The openness of jazz allows for the adaptation of elements from many musical traditions.

But the highly developed Indian tala systems also use many other rhythms, like those based on fives beats, seven beats, nine beats, and more. In addition to these others, the familiar 4/4 and 3/4 type rhythms in Indian music are developed to a high degree of subtlety and complexity rarely seen in Western music prior to their introduction.

Certain styles of modern jazz, such as fusion, have incorporated these rhythmic ideas, and musicians like guitarist McLaughlin, keyboardists Jan Hammer and Brad Meldau, and drummers Steve Smith and Trilok Gurtu are masters at this type of playing. The openness of jazz allows for the adaptation of elements from many musical traditions, and this is one area where Indian music has been greatly influential.

Drummers and percussionists can easily find common ground, since rhythm and pulse are so universal to music. The formidable jugal-bandis (duets) between mridangam player Trichy Sankaran and Latin percussionist Giovanni Hidalgo are very exciting, as were the jugal-bandis between tabla master Alla Rakha and jazz drummer Buddy Rich, a generation ago.

Artists and influence.

In addition to those mentioned above, there are a number of other jazz artists and composers whose body of work reflects the continuing influence of Indian music. I count myself among them. Some names are immediately recognizable, and they all have made significant contributions to the idiom.

The list includes: trumpeters Miles Davis, Maynard Ferguson, and Jon Hassell; drummers Steve Smith, Billy Cobham, Tom Rainey, Frank Bennett, and Dan Weiss; composer/pianists Terry Riley and La Monte Young, Keith Jarrett, and Marc Rossi; bassists Miroslav Vitous, Ratzo Harris, Jaco Pastorius, and Jack Bruce; saxophonists Yusef Lateef, John Handy, Phill Scarff, and Steve Gorn; percussionists Bob Becker, and Jamie Haddad; guitarists Pat Metheny, Larry Coryell, R. Prasanna, and David Lindley, to name just a few.

These musicians cover the whole gamut of Indian influences—from the obvious, to the more subtle. Occasionally, as with Miles Davis, they are simply one element of a multicultural melange.

The future.

It has been said that jazz is about freedom, and how the artist controls that freedom is a testament to his or her skill. As jazz writer Eric Nisenson says in his provocative book Blue, The Murder of Jazz:

This is one reason it [jazz] is such a remarkable music---it is open to an endless variety of fusion and infinite possibilities, like the country in which it was born. Or at least like that country used to be.

Indian music has strict guidelines (as does some jazz) and how the artist finds freedom within those guidelines is a testament to his or her skill. Based on these simple truths, it is only natural that Indian music will continue to influence jazz, in as many ways as the artist's imagination will allow.

We can also add to this the huge influence Indian film music is having on Western music today. The composer AR Rahman alone, who did the soundtrack to Slum Dog Millionaire, is having as much an influence on Western film and popular music as anyone in Hollywood.

The great Malian Afro-pop singer Salif Keita put it best. When once asked if he thought Westerners were borrowing too heavily from African music, he replied: "If you hear something once, and it moves you, it becomes a part of you." What better way to show the universality of music?

1, 2 Porter. Lewis, John Coltrane: His life and music. U. of Michigan Press, 1999. P 211

3 Khan, Ashley, A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane's Signature Album. Penguin Books, 2002, P 58