- Published May 3, 2013 in In The Studio

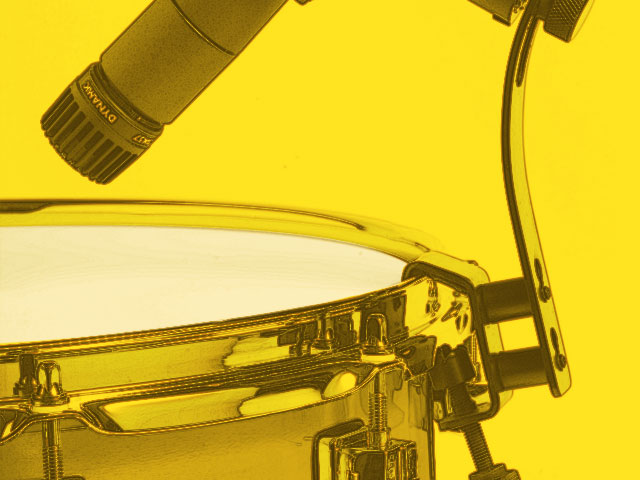

Mic’ing your drums can make or break a mix. And because there are so many variables, it often turns out to be the trickiest part of your session.

There’s a time to use loops and samples and a time not to. For those who want the real thing, the mind boggles at the number of ways to mic a drum kit. It’s as important to know the room sound you’re recording in as it is to know the kit and the player’s vibe playing it. It’s also helpful to know what you want the drums to sound like in the final mix (ambient, lo-fi, trashy, clean, etc.).

Get ready.

If you can, before you start recording (in your own free time before sessions start) walk around the room, clap your hands, snap your finger and listen to find the most pleasing position–dead or live, mid reflections or lots of lows. In most rooms this can be incredibly subtle stuff. Now take a selection of mics (condenser, ribbon, dynamic) and line them up together in the room as a drummer plays a simple groove.

Listen back.

Record the mics and compare, make some notes on the positioning and then move the mics to another position in the room. Repeat. Especially try the mics close to the kit and at different heights. At the end of this process you will have a very good idea how your room responds to a drum kit, and a very good starting point for mic’ing.

How many mics you use depends on how many you have, what kind of mics and what sound you’re going for. If you only have a couple of mics then you’ll be looking for an overall vibe of the kit as opposed to close mic’ing. If you have more mics, you can do more which will give you more options later.

Give the drummer some.

If the drummer is smashing the crap out of their hi hats, feed more into the headphones or dampen them. A lot of drummers will do this in order to keep time, especially when playing to a click.

As a matter of fact, if a drummer is over hitting anything, the end effect will be to choke the sound. Bonham hit hard but he never hit so hard as to choke the life out of the drum or cymbals. When in doubt, draw a silver dollar sized circle at the center of the snare – if the drummer isn’t hitting inside that circle on the heavy hits then good luck trying to get a consistent snare sound when mixing.

In Part 2 we’ll look at some different mics and the classic techniques used for early rock, like the Glyn Johns method and the “Ringo sound”.