- Published Dec 19, 2013 in Gear Garage

Wondering how records are actually made? As vinyl comes back into fashion, it's worth taking a look at the process with one of the biggest names in the biz.

One of the most sought after vinyl-cutting systems in the world is the nearly indestructible VMS-70 and VMS-80 cutting systems built by Neumann. The VMS-82 was the last of these produced. I’m thankful to say that we get to use our VMS-82 lathe every day to cut lacquers for clients around the globe.

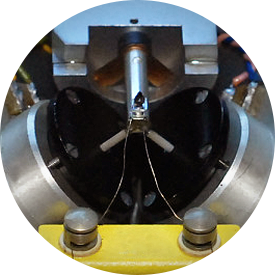

The actual cutting happens at the cutter head. In this case, the BMW of cutter heads, the SX-74.

Though it was initially built in 1974, this design was never dramatically improved. It was capable of cutting with sufficient level and flat frequency response to please nearly everyone.

The underside of a SX-74 cutter head.

A closer look.

The two round “cans” on either side are the voice coils. You can also see the cutting stylus: a faceted sapphire glued to a pin that mounts in the tube that connects to each voice coil. Also in the foreground are two fine wires. These carry a small voltage that heats the stylus to an optimal temperature so that it slices smoothly through the lacquer instead of dragging and causing extra noise from a jagged cut.

The drive coils of the stereo cutter head are mounted at right angles. When there is audio in the left channel, the left coil goes in and out just like a speaker does. And when there is audio in the right channel, the right coil goes in and out. One voice coil in the cutter head is wired out of phase on purpose so that, when a mono signal is cut, the left coil is moving in as the right coil is moving out. Thus, a mono signal cuts a lateral groove.

The Neumann VMS-80 with SX-74 cutter head remains a gold standard in vinyl-cutting systems.

Why is it done this way?

We have to go back to mono to find out. Early records—initially 78s and then LPs—were mono. Systems that cut mono records had only one drive coil and it moved the cutting stylus back and forth creating a lateral, constant-depth groove. There was little concern about the depth of the cut as long as it was deep enough to hold the playback stylus in the groove.

Then along came stereo. Researchers needed to find a way to carve two channels of audio into a record but make the new technology compatible with mono records and players.

Unfortunately, today’s technology designers don’t put quite so much effort into forward- and backward-compatibility. But that’s a soapbox speech for another time.

So what they came up with was to record the mono component of the stereo audio laterally—like on a mono record. Then, by adding a second coil and wiring it out of phase with the first coil, they created depth modulation which records the stereo or side signal.

Going deeper.

Researchers needed to find a way to carve two channels of audio into a record but make the new technology compatible with mono records and players.

Stereo is made up of a left signal and a right signal. OK, that’s simple. But stereo can also be described as the "mono component" (everything that is exactly the same in both speakers) and the "difference component" (everything that is different). This is commonly called Middle and Side, or M-S for short.

A stereo signal can be converted into an M-S signal and back again with nearly no change at all. FM radio is transmitted in M-S. The middle signal is a strong full-wave signal. And it is this signal that you hear when you are far away from the radio tower.

That signal is mono. As you get closer to the radio tower, your radio can tune in the sub carrier signal, which carries the difference (side channel). When you receive a strong enough signal, the FM station now plays back in full stereo because it has both the middle and the side signals.

It can be hard to believe because we commonly think in "left and right" rather than "middle and side". But it’s true. It’s a matter of physics and alternating current electronics.

The groove shows us the difference signal by it’s depth. So a mastering engineer says “lateral” and means the mono (or, middle) signal. And when the engineer says “vertical” he or she is referring to the difference(or, side) signals.

Once you have a hold of that concept, we can start to talk about why some records seem to make the vocals spitty and sibilant. And why some recordings have to be modified with equalization to minimize out-of-phase bass.

But there is one more thing to understand before we can control our quality. It was a standard developed in the 1950s called the RIAA Curve.

Next week I'll talk about what the RIAA curve is, why it was standardized, and what steps we have to take to make records sound really good.